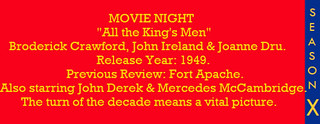

Review #1373: All the King's Men.

Review #1373: All the King's Men.Cast:

Broderick Crawford (Willie Stark), John Ireland (Jack Burden), Joanne Dru (Anne Stanton), John Derek (Tom Stark), Mercedes McCambridge (Sadie Burke), Shepperd Strudwick (Adam Stanton), Ralph Dumke (Tiny Duffy), Anne Seymour (Mrs. Lucy Stark), Katharine Warren (Mrs. Burden), Raymond Greenleaf (Judge Monte Stanton), and Walter Burke (Sugar Boy) Directed, Written and Produced by Robert Rossen (#702 - The Hustler)

Review:

One can hope to make at least one great film or at least hope to be part of a prestige picture worth talking about. This is a film to be proud of in terms of its directing and acting. Robert Rossen directed just ten films before his death at the age of 57, but he managed to make films in a variety of genres successfully, such as noir, drama and thriller. He had gone from hustling pool as a youth to being a stage manager, with the passage of time leading to him writing and directing his own plays. He went to Hollywood as a screenwriter after being discovered by Mervyn LeRoy of Warner Brothers in 1936. In the eleven years that followed before his directorial debut, he served as a writer for a few films along with being chair of the Hollywood Writers Mobilization during World War II. He jumped around a few studios before finding himself with Columbia Pictures. If you can believe it, Crawford was not the first choice for the main role. It was actually John Wayne who was offered the role first. He angrily rejected the role in a letter, calling the script an acidic one on the "American way of life" (among other statements that make me roll my eyes). The son (and grandson) of vaudevillians, Crawford found himself on stage and film by the time he was in his twenties, with usual roles being in B-moves or in supporting roles. It was this film that he became a star, and he would later find himself with further notability with Highway Patrol in the following decade.

The film was based off the 1946 novel of the same name by Robert Penn Warren, which had won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction the following year. There has been considerable discussion about the novel over its themes and inspirations, with the most notable being over the resemblance of its main character to governor/senator Huey Long, since Warren had taught at Louisiana State University at the time of Long's unexpected death, although Warren once said that book was never intended to be a book about politics, since to his eyes it merely served as a provider to the framework story to work out the deeper concerns. The book has had two further adaptations, in terms of an opera (named after the lead character), and a 2006 adaptation from Steven Zaillian that attempted to be more faithful to the novel that changed the setting to the early 1950s.

One is swept into the film fairly quickly, a drama that plays like a noir with a sense of urgency and furor that sweeps a viewer away in making compelling entertainment. Crawford proves to be a master of intimidation, one who leaves an imprint on you every time he appears, a presence that strikes at you with all of his might that has the right mix of brashness alongside insecurity. Ireland follows along just fine, an observer of the noir kind that we follow through his brooding eyes. Dru and Derek accompany him just as carefully. McCambridge (a noted radio actress in her debut) proves to be quite electrifying, a hardboiled presence that resonates with rough versatility. The others prove to be worthy supporting presences that seem like pawns in the hands of material that desires as such. It is an urgent film, wrapped in cynical honesty that still works in relevancy for the most part after seven decades. The biggest achievement is that the film came out the way it did at all. There were problems in whittling the film to salvageability because of how much footage Rossen shot. Editor Al Clark could only edit it down to 250 minutes (in part because of Rossen's reluctance to really cut anything), so it fell to the hands of Robert Parrish to help with edits. Together, Rossen and Parrish agreed to edit the film like a series of impressions, where they would roll the film on the synchronizer and find the center of each scene and cut arbitrarily 100 feet before and after each center, regardless of dialogue or music. The result is a 110 minute quickfire winner. The film was certainly a deserving hit, and it later won for Best Picture at the Academy Awards the following year, beating out such films like A Letter to Three Wives (which won director-writer Joseph L. Mankiewicz awards over Rossen for directing and writing) for the main prize alongside Crawford and McCambridge. On the whole, this is a film that has plenty of blunt force in terms of what it wants to say about the nature of power and how one can find themselves ensnared in the same traps they held others to if they reach that point, headlined by Crawford and his domineering presence that makes this a fair one to recommend.

Overall, I give it 9 out of 10 stars.

And now, the list for next month. Several faces join the crowd for the 1950s, a mix of directors and stars that have either been covered before or haven't before, complete with a rollout of world cinema debuts.

Review #1372: Fort Apache.

Review #1372: Fort Apache. Review #1371: Unconquered.

Review #1371: Unconquered. Review #1370: Life with Father.

Review #1370: Life with Father. Review #1369: Duel in the Sun.

Review #1369: Duel in the Sun. Review #1368: The Best Years of Our Lives.

Review #1368: The Best Years of Our Lives. Review #1367: A Matter of Life and Death.

Review #1367: A Matter of Life and Death. Review #1366: The Stranger.

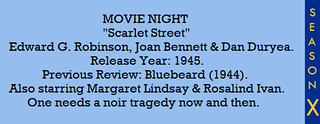

Review #1366: The Stranger. Review #1365: Scarlet Street.

Review #1365: Scarlet Street. Review #1364: Bluebeard.

Review #1364: Bluebeard.

Review #1362: Now, Voyager.

Review #1362: Now, Voyager.

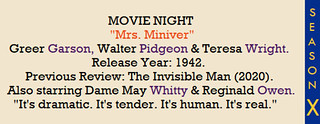

Review #1360: Mrs. Miniver.

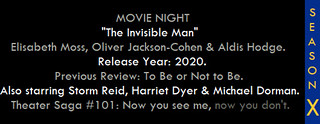

Review #1360: Mrs. Miniver. Review #1359: The Invisible Man.

Review #1359: The Invisible Man.